Read the original article from The Sacramento Bee by Victoria Dalkey.

How do you explain a woman named Maria?

Born Barbara Pincus in 1928 in Brooklyn, she was a petite, dark-haired dynamo who came to California as a postwar bride with her husband Frank Taffet. She had three children, worked as a schoolteacher and social worker, and became a Sacramento art collector and gallerist. Her Jennifer Pauls Gallery represented some of Sacramento’s strongest artists from the 1970s and 1980s.

After her husband’s sudden death in 1973, Barbara Taffet reinvented herself as Maria Alquilar, a Latina artist whose fictive back story included a Sephardic Jewish father from Argentina. Drawing on her deep knowledge of world myths and spiritual traditions, filtered through her own personal mythology, she began creating idiosyncratic works inspired by the work of the Sacramento-Davis area narrative expressionist, outsider and funk artists she admired and collected.

After a move to Santa Cruz in 1986, she embarked on a career as a successful public artist who did works in Sacramento, San Francisco, San Jose and Denver, including “Port of Entry,” an award-winning piece in San Luis, Ariz., that was commissioned by the General Services Administration’s Art in Architecture program. In 1999, she moved to Miami where she immersed herself in Afro-Cuban culture, basing a number of exotic works on Haitian Vodou rituals, as well as producing vibrant images celebrating Cuban marketplaces and festivals.

In 2014, she returned to Sacramento to be near her daughter Gilda Taffet, a talented Sacramento musician and composer. In frail health, she died that year at the age of 86, leaving behind a substantial body of paintings, ceramics, metal sculptures and prints, 50 of which are on view at JAYJAY Gallery in East Sacramento.

Blending diverse sources — from Russian icons, reflecting her Russian Jewish heritage, to Mexican retablos, reflecting her adopted identity — Alquilar’s richly imagined, paintings and ceramics at JAYJAY live up to the gallery’s billing of the show as “the art event of the summer.”

Many of Alquilar’s works are stunning examples of the kind of personal myth-making we associate with Roy De Forest, David Gilhooly, Maya Peeples-Bright, Anne Gregory and Joan Brown in her later works. It is as if after the premature loss of her husband, she adopted a persona that gave her permission to do the work she was meant to do and allowed her to reach her full potential as an artist.

For me, her strongest works have a dark edge that adds complexity to her intricately wrought, highly individual amalgam of sources that result in what California State University, Sacramento, art history professor, Elaine O’Brien, calls “an American woman’s book of illuminated fables for the turn of the millennium and the beginning of the global era.”

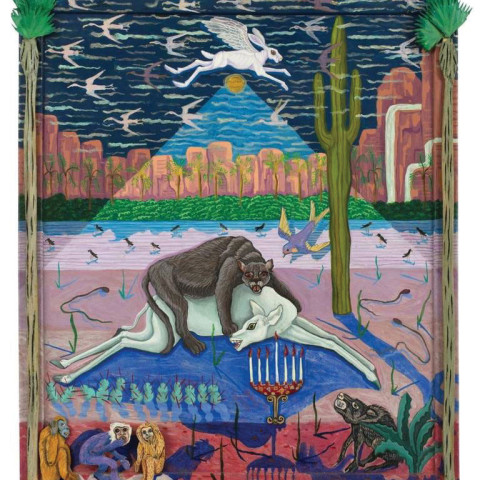

“Dreamstealers,” 1992, her large-scale mixed media work, combining painting and sculpture, is a masterwork, in which a white deer, symbolizing the artist, is threatened by a menacing panther and monkey-assassins armed with with bows and arrows. It is, Alquilar wrote, her “interpretation of people who belittle and discourage our dreams of success, love, creativity, and happiness.”

In “Loved to Death 1: The Embrace,” 1988, an even darker image, the panther, symbolizing the kind of selfish love that robs the loved one of life, has attacked the deer, holding it in its sharp claws, pressing heavily on its back, like a molesting angel. At the bottom of the disturbing image, a trio of “See No Evil” monkeys looks out at the painting’s viewers making them complicit in their failure to face the truth.

Alquilar’s fascination with Native American cultures is the source for “Zuni Series: The Dancehall of the Dead,” 2000, which vibrantly depicts kachina dancers who impersonate the true kachinas or spirit beings who dwell in the dark underworld in a tribal myth that echoes shamanic traditions in many cultures and literary works, from Homer’s “Odyssey” to the Hebrew Bible.

Again referencing her adopted persona “And With What Body Do They Come: Los Desaparecidos,” 1991, which memorializes the terrible fate of Latin American dissidents and innocent civilians arrested by military governments never to be seen again. Coming full circle, she returns to her Eastern European Jewish heritage in “Kristallnacht,” 2009, a painting with a shattered surface that depicts the horrors of the Holocaust. Both remind us of her lifelong solidarity with victims of oppressive and murderous regimes.

Lighter in spirit are large ceramic plates like “Atlantis,” in which archaic Greek figures from myth roil in sea waters, and “Blood Wedding,” an homage to the evocative play by Spanish poet Francisco Garcia Lorca. The former reminds me of the lush and playful Majolica vessels in the collection of San Francisco’s Legion of Honor Museum., the latter of funk era story platters.

This is a show that gives a sometimes overlooked artist with Sacramento roots the kind of attention her work deserves. You won’t want to miss it.

‘LOVED TO DEATH: A RETROSPECTIVE OF WORK BY MARIA ALQUILAR’

Where: JayJay, 5520 Elvas Ave., Sacramento

When: Through July 29th, 2017. Wednesday – Saturday 11 – 4pm

Cost: Free